Statistical Disclosure Control (SDC): An Introduction¶

Need for SDC¶

A large part of the data collected by statistical agencies cannot be published directly due to privacy and confidentiality concerns. These concerns are both of legal and ethical nature. SDC seeks to treat and alter the data so that the data can be published or released without revealing the confidential information it contains, while, at the same time, limit information loss due to the anonymization of the data. In this guide, we discuss only disclosure control for microdata. [1] Microdata are datasets that provide information on a set of variables for each individual respondent. Respondents can be natural persons, but also legal entities such as companies.

The aim of anonymizing microdata is to transform the datasets to achieve an “acceptable level” of disclosure risk. The level of acceptability of disclosure risk and the need for anonymization are usually at the discretion of the data producer and guided by legislation. These are formulated in the dissemination policies and programs of the data providers and based on considerations including “[…] the costs and expertise involved; questions of data quality, potential misuse and misunderstanding of data by users; legal and ethical matters; and maintaining the trust and support of respondents” (DuBo10). There is a moral, ethical and legal obligation for the data producers to ensure that data provided by the respondents are used only for statistical purposes.

In some cases, the dissemination of microdata is a legal obligation, but, in most cases, the legislation will formulate restrictions. Thus, a country’s legislative framework will shape its microdata dissemination policy. It is crucial for data producers to “ensure there is a sound legal and ethical base (as well as the technical and methodological tools) for protecting confidentiality. This legal and ethical base requires a balanced assessment between the public good of confidentiality protection on the one hand, and the public benefits of research on the other. A decision on whether or not to provide access might depend on the merits of specific research proposals and the credibility of the researcher, and there should be some allowance for this in the legal arrangements.” (DuBo10).

“Data access arrangements should respect the legal rights and legitimate interests of all stakeholders in the public research enterprise. Access to, and use of, certain research data will necessarily be limited by various types of legal requirements, which may include restrictions for reasons of:

- National security: data pertaining to intelligence, military activities, or political decision making may be classified and therefore subject to restricted access.

- Privacy and confidentiality: data on human subjects and other personal data are subject to restricted access under national laws and policies to protect confidentiality and privacy. However, anonymization or confidentiality procedures that ensure a satisfactory level of confidentiality should be considered by custodians of such data to preserve as much data utility as possible for researchers.

- Trade secrets and intellectual property rights: data on, or from, businesses or other parties that contain confidential information may not be accessible for research. (…)” (DuBo10).

Box 1, extracted from DuBo10, provides several examples of statistical legislation on microdata release.

Info-box - Examples of statistical legislation on microdata release

- The US Bureau of the Census operates under Title 13-Census of the US Code. “Title 13, U.S.C., Section 9 prohibits the publication or release of any information that would permit identification of any particular establishment, individual, or household. Disclosure assurance involves the steps taken to ensure that Title 13 data prepared for public release will not result in wrongful disclosure. This includes both the use of disclosure limitation methods and the review process to ensure that the disclosure limitation techniques used provide adequate protection to the information.”

Source: https://www.census.gov/srd/sdc/wendy.drb.faq.pdf

- In Canada the Statistics Act states that “no person who has been sworn under section 6 shall disclose or knowingly cause to be disclosed, by any means, any information obtained under this Act in such a manner that it is possible from the disclosure to relate the particulars obtained from any individual return to any identifiable individual person, business or organization.”

Source: http://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/S-19/page-2.html

Statistics Canada does release microdata files. Its microdata release policy states that Statistics Canada will authorise the release of microdata files for public use when:

- the release substantially enhances the analytical value of the data collected; and

- the Agency is satisfied all reasonable steps have been taken to prevent the identification of particular survey units.

In Thailand the Act states: “Personal information obtained under this act shall be strictly considered confidential. A person who performs his or her duty hereunder or a person who has the duty of maintaining such information cannot disclose it to anyone who doesn’t have a duty hereunder except in the case that:

- Such disclosure is for the purpose of any investigation or legal proceedings in a case relating to an offense hereunder.

- Such disclosure is for the use of agencies in the preparation, analysis or research of statistics provided that such disclosure does not cause damage to the information owner and does not identify or disclose the data owner.”

Source: http://web.nso.go.th/eng/en/about/stat_act2007.pdf section 15.

Besides the legal and ethical concerns and codes of conducts of agencies producing statistics, SDC is important because it guarantees data quality and response rates in future surveys. If respondents feel that data producers are not protecting their privacy, they might not be willing to participate in future surveys. “[…] one incident, particularly if it receives strong media attention, could have a significant impact on respondent cooperation and therefore on the quality of official statistics” (DuBo10). At the same time, if data users are unable to gain enough utility from the data due to excessive or inappropriate SDC protection, or are unable to access the data, then the large investment in producing the data will be lost.

The risk-utility trade-off in the SDC process¶

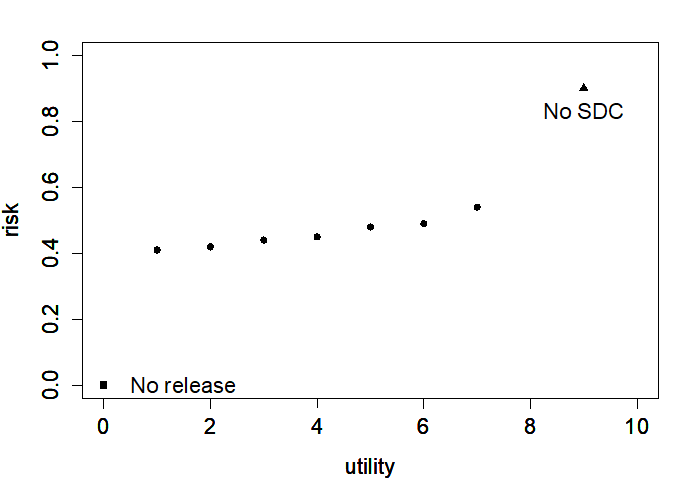

SDC is characterized by the trade-off between risk of disclosure and utility of the data for end users. The risk–utility scale extends between two extremes; (i) no data is released (zero risk of disclosure) and thus users gain no utility from the data, to (ii) data is released without any treatment, and thus with maximum risk of disclosure, but also maximum utility to the user (i.e., no information loss). The goal of a well-implemented SDC process is to find the optimal point where utility for end users is maximized at an acceptable level of risk. Fig. 1 illustrates this trade-off. The triangle corresponds to the raw data. The raw data have no information loss, but generally have a disclosure risk higher than the acceptable level. The other extreme is the square, which corresponds to no data release. In that case there is no disclosure risk, but also no utility from the data for the users. The points in-between correspond to different choices of SDC methods and/or parameters for these methods applied to different variables. The SDC process looks for the SDC methods and the parameters for those methods and applies these in a way that reduces the risk sufficiently, while minimizing the information loss.

Fig. 1 Risk-utility trade-off

SDC cannot achieve total risk elimination, but can reduce the risk to an acceptable level. Any application of SDC methods will suppress or alter values in the data and as such decrease the utility (i.e., result in information loss) when compared to the original data. A common thread that will be emphasized throughout this guide will be that the process of SDC should prioritize the goal of protecting respondents, while at the same time keeping the data users in mind to limit information loss. In general, the lower the disclosure risk, the higher the information loss and the lower the data utility for end-users.

In practice, choosing SDC methods is partially trial and error: after applying methods, disclosure risk and data utility are re-measured and compared to the results of other choices of methods and parameters. If the result is satisfactory, the data can be released. We will see that often the first attempt will not be the optimal one. The risk may not be sufficiently reduced or the information loss may be too high and the process has to be repeated with different methods or parameters until a satisfactory solution is found. Disclosure risk, data utility and information loss in the SDC context and how to measure them are discussed in subsequent chapters of this guide.

Again, it must be stressed that the level of SDC and methods applied depend to a large extent on the entire data release framework. For example, a key consideration is to whom and under what conditions the data are to be released (see also the Section Release types). If data are to be released as public use data, then the level of SDC applied will necessarily need to be higher than in the cases where data are released under license conditions to trusted users after careful vetting. With careful preparation, data may be released under both public and licensed versions. We discuss how this might be achieved later in the guide.

| [1] | There is another strand of literature on the anonymization of tabular data, see e.g., HDFG12. |

References

| [DuBo10] | Dupriez, O., & Boyko, E. (2010). Dissemination of Microdata Files; Principles, Procedures and Practices. International Household Survey Network (IHSN). |

| [HDFG12] | Hundepool, A., Domingo-Ferrer, J., Franconi, L., Giessing, S., Nordholt, E. S., Spicer, K., et al. (2012). Statistical Disclosure Control. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons Ltd. |